In

our series on contagious alternatives, concrete utopias, paradigmatic cases,

positive news, actions to learn from, small revolutions or revolutions in

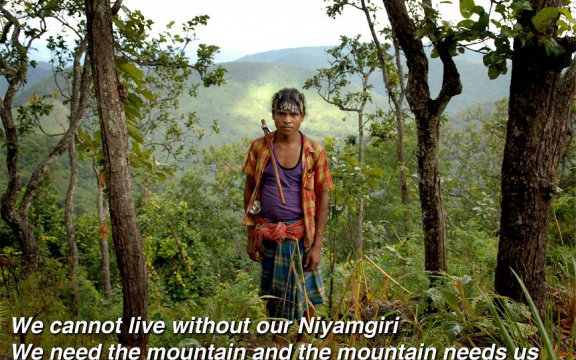

reverse, here an Indian Avatar (see pictures underneath!)… A fairytale for

activists, an example to feed upon concerning this most urgent of issues: the defense of the commons…

by Ranjani Balasubramanian

In the dense

forested heartland of India is the state of Odisha. Extending from the

beautiful Eastern coast of India along the Bay of Bengal, into the western edge

of the Deccan Plateau, the recorded history of civilization in the state spans

over 5000 years, and yet it is home to some of the most stunning and untouched

landscapes both along the sea and in pristine inland forests. The hills of

Odisha, since time immemorial, have been home to the adivasis (the first

dwellers), who are believed to predate even Vedic culture and society. Literary

works as old as the Mahabharata refer to the tribes as sovereign communities of

the forest.

Being proud and

ferocious people, they have always defended their life and land. Hindu society

reacted to their otherness by often casting the adivasis as forest dwelling

animists, while at the same time, leaving the regions inhabited by them largely

outside the rule of the regency to be managed by their own indigenous forms of

self-governance. They have thus continued through the millennia to live outside

of the structured mainstream society by developing a convivial nomadic life in

the hills and forests of India.

The Dongaria

Kondhs are one of the many Odisha tribes; a population of 8000 people who

inhabit the slopes of the Niyamgiri hill range along the western border of the

state. Niyamgiri is an area of densely forested hills, deep gorges and

cascading streams. The Dongria Kondhs farm the hills’ fertile slopes, harvest

their produce, and worship a living mountain god Niyam Raja and the hills he

presides over, including the 4,000 meter ‘Mountain of the Law’, Niyam Dongar[1].

Dharanima, the

earth goddess is also worshipped as a complement to the God of the Mountains and

it is believed that these male and female principles come together to grant the

Kondhs prosperity, fertility and health[2].

Their belief in the sacredness of the hills is rooted in a strong dependence on

the natural resources that the mountains provide. The Dongaria Kondhs are proud

of their economic independence and freedom from want.

Culturally and

ecologically the Niyamgiri hills are extremely rich and diverse. Niyam Dhongra

is the water source for both the Vasandhara River and a major tributary of the

River Nagavalli. The fauna includes a number of rare species of plants and

medicinal herbs. The forests of the Dongaria Kondhs are home to a number of

endangered wildlife species like tigers, sloth bears, giant squirrels,

leopards, langur, sambhar and mouse deer. It is also the territory of the Royal

Bengal Tiger and a migratory corridor for elephants[3]

and has been proposed as a wildlife sanctuary in 1998 by the Indian Ministry of

Environment and Forests.

These pristine

hills however have one more secret. Under this magnificent surface are huge

deposits of high grade bauxite- the raw material used to produce aluminum.

Odisha is a state that is bestowed with huge mineral deposits and since the

liberalization of the Indian economy in the 90’s, the extractive industry has

been closing in on the ecologically fragile state. The Odisha government, keen

to cash in on this bounty, has been promoting resource intensive development

models in the state.

In 2004, in

spite of the the human and ecological circumstances, the Odisha government

signed an agreement with Vedanta Aluminia, a multinational mining corporation

ironically named after a Hindu school of philosophy which emphasizes the unity

of all forms of life, to mine bauxite in the Niyamgiri hills. This would be complemented

by setting up an aluminum refinery at the foothills. To support this agreement,

large tracts of agricultural land were usurped from the tribes at the foothills

and an aluminum refinery was already set up at Lanjigarh[4].

The proposal for the open cast bauxite mine on the top of the Niyamgiri hills

was especially harsh to the tribes, for, according to their cultural and

religious beliefs the hilltop was the abode of their living God Niyamraja. As

often is the case their religious belief tied in with a very crucial ecological

aspect that the mountaintop was the source of water for the whole region.

Fuelled by this

assault on their home and religion, the Dongaria Kondhs took up massive

protests against Vedanta steel. Joined by activists and NGO’s they went to the

judiciary for relief. To understand the rest of this story, we must make a

small digression to explain the constitutional and legal position of the forest

dwelling tribal peoples in India.

Tribal people

constitute 8.61% of the total population of the country, numbering 104.28

million (2011 Census) and cover about 15% of the country’s area[5] (scattered

across the country and forming thousands of different tribes each with unique

cultures). In spite of this large presence, their interests have been often

undermined or altogether neglected.

In historical

India, the tribal peoples have always been recognized as sovereign. Even while

the forests were under the domain of the local rulers, the rights of the tribes

to the forests were always granted. However the British occupation, prompted by

the global demand for timber, regularized land ownership and asserted colonial claim

over the forests while criminalizing the traditional resource management

systems. This policy was most devastating to the tribal population, who were

restricted from free access to the forests, leading to over two centuries of

oppression and exploitation of tribal people.

During the

post-independence consolidation of the Princely States into the Republic of

India, under the land reforms, feudal and royal lands were proclaimed as

reserve forests, but the issue of tribal land rights was not addressed- an

oversight that led to numerous land conflicts between the non-tribal and tribal

populations[6].

One of the

colonial features of the independent Indian State was its imposition of

techno-scientific expertise over people’s traditional knowledge and management

systems as the only way to achieve its national development goals. Therefore,

even up until the 1990s the restrictions on the tribal access to land not only

continued but were exacerbated by laws such as The Wildlife Protection Act

1972.

After decades of

struggle for tribal rights starting with tribes from central India snowballed

into a national movement for tribal rights, the issues were brought up under

the review of the Indian judiciary in a number of litigations. The Supreme

Court of India in the first years of 2000, ruling in an important case of

evictions held that the tribes “have a definite right over the forest”[7] and

that diversions or evictions should be undertaken only with their consent.

This landmark

case led the Government of India to admit to the need to address a ‘historical

injustice’ against the forest dwellers of the country[8].

In 2006 the Forest Rights Act[9]

was passed which brought sweeping recognition and support for the forest

dwellers and their rights to the forest. However, the most significant aspect

of the bill was that the final authority for diversion of forestland for

non-forest use rested with the Gram Sabha. The gram sabha, or village council

in this case consisted of every member of the village unit, as opposed to a

council of representatives. Thus, the forest dwellers were given the direct democratic

authority to decide the future of their forests.

It is important

to know this legal history because in India, time and again, the cause of the

commons has been able to gain a foothold only because of the backing of the

judiciary[10].

In terms of social justice and progressive reforms, the Indian judiciary has

often been an under-recognized superhero.

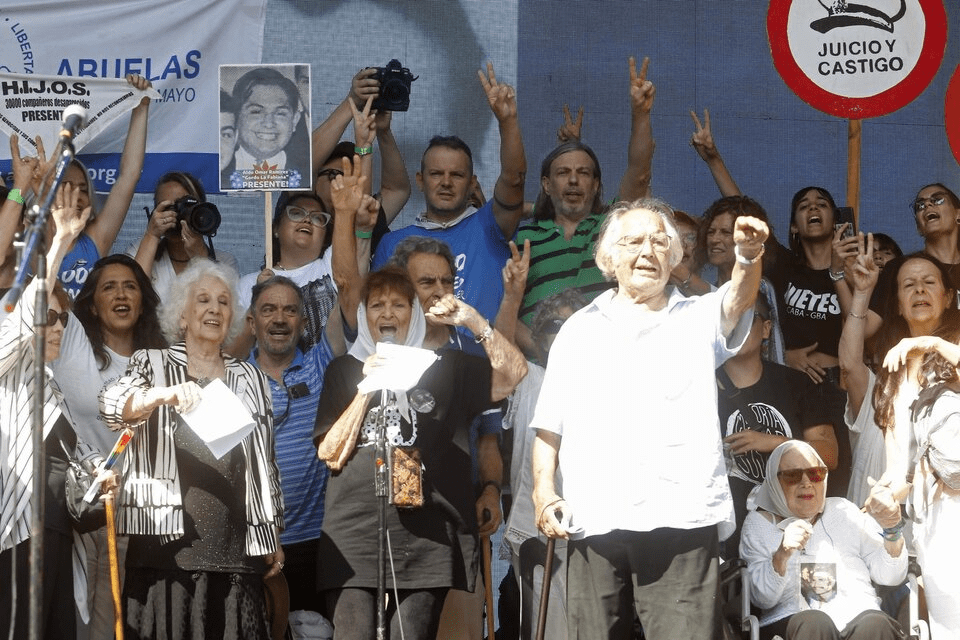

Back in the

Niyamgiri hills, the tribe faced the full might and corruption of the State Government

and Vedanta Alumina while protesting vehemently against the destruction of

Niyamgiri. The protests gathered national and international campaigners and

were even endorsed as the real version of James Cameron’s Avatar. The

protracted legal battle raged on in the courts even as Vedanta strong-armed

their way ahead with construction of roads and access routes to the hills,

without waiting for any sort of environmental clearance. This led to a number

of violent clashes between the Kondhas and the police. When these blatant

misrepresentations and illegalities were brought to light, the Ministry of

Environment was under enormous public pressure and had to stall the

environmental clearance of Vedanta.

After nearly a

decade of resistance, in a landmark ruling in January 2014, the Supreme Court

of India rejected an appeal to allow Vedanta Resources to mine the Niyamgiri

hills. In a complex judgment, the court decreed that those most affected by the

proposed mine should have a decisive say in whether or not it goes ahead. As

per the fundamental provisions The Right to Religious Freedom, the Court

recognized that the Dongria Kondh’s right to worship their sacred mountain must

be ‘protected and preserved’, and that those with religious and cultural rights

must be heard in the decision-making process. The tribe was given three months

to decide whether to allow the mining of their sacred hills. The ruling, for

the first time in India, forced a multi-billion dollar corporation to go to each

of the twelve Gram Sabhas (village councils) of about 1500 forest dwellers, and

put forward their pleas to undertake mining in the form of a referendum

overseen by the Supreme Court of India.

In spite of

months of incitement, violence, intimidation and pressure exerted on the tribe

by the government and by Vedanta before the referandum, all 12 tribal councils

unanimously voted against the mining bid. The final say lay with the Ministry

of Environment and Forests who proceeded to nullify the mining rights of

Vedanta in the Niyamgiri hills[11].

In May 2014

Vedanta officially announced that: “In deference to the sentiments of the

community, Vedanta confirms it is not seeking to source bauxite from Niyamgiri

bauxite deposit for its alumina refinery operations, and will not do so until

we have the consent of the local communities.”[12] Victory

for the First Dwellers!

But….the

aluminum refinery however remains operational and works on the capacity of the

local Niyamgiri mine and in August 2014 Vedanta has sought permission to expand

the facility. As of 2014 the state of Odisha still has over 300 applications[13]

for mineral extraction waiting to be cleared- and unfortunately to extract

these minerals whole ecologies also need to be cleared.

Ranjani

Balasubramanian is an architect from

India, who did a postgraduate master on human

settlements at the Department of architecture in Leuven. She did a thesis on

urban activism in Bangalore in the series ‘towards an Atlas of the commons’

with a certain prof. Lieven De Cauter. Her masterthesis for the MAHS-MAUSP program

can be downloaded: soon…

[1] The word for

mountain translates as ‘Dongar’- from which the Dongaria Kondh receives their

name- the people of the mountains.

[2] ‘Report of

the four member committee for investigation into the proposal submitted by the

Orissa Mining Company for bauxite mining in Niyamgiri’, dated August 16, 2010,

by Dr N C Saxena, Dr S Parasuraman, Dr Promode Kant, Dr Amita Baviskar.

Submitted to the Ministry of Environment & Forests, Government of India.

[3] Geetanjoy Sahu,

‘Mining in the Niyamgiri Hills and Tribal Rights’, 2008

[4] It was

later discovered that the refinery was set up even before the clearances was

made and it was in blatant violation of environmental norms.

[6] Sanjoy

Patnaik ‘Rights Against All Odds: How Sacrosanct is Tribal Forest Rights?’

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The

Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest

Rights) Act, 2006

[10] On the crucial role the law can play in the defense of the commons,

see Peter Linebaugh’s seminal book, The Magna

Carta Manifesto, Liberties and commons

for all. University of California

Press, 2008. He proves that attached to Magna

Carta (1215) there was the ‘Charter of the Forest’, that was the foundation of

the entire idea of legal rights to the use of the forest as natural commons. Crucial

really. The law is not necessarily on the side of private property, as anarchists

and Marxists claim, on the contrary rather: the law is the foundation, the

ultimate defence of the common. Magna Carta is really a law as social contract

between the sovereign and the commoners [editor’s note, LDC]

[11] http://www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/dongria

[12] Siddhartha

P Saikia, ‘Govt rejects Vedanta’s Niyamgiri mining project’ published in

Business Line, January 12, 2014

[13] Business Standard,

‘Odisha sitting over 300 PL bids for bauxite mining’, July 25, 2014

“Franse kernenergie? Ongelooflijk dat hun leugencam...

“Franse kernenergie? Ongelooflijk dat hun leugencam...